Hope and growth. Those two words have changed George K. L. Smith’s life and the lives of other formerly incarcerated individuals who have decided to use their experiences as a bridge rather than a wall.

Tucked away on a quiet street is a former convent where the Academy of Healing Opportunities and Personal Enrichment, or HOPE, now resides. An arm of the drug, alcohol and mental health treatment nonprofit Options Recovery Services and dreamt up by Options’ Executive Director Justin Phillips, the center is a reentry home and support system for men who are exiting prison as state-certified drug and alcohol counselors.

The space – with its large dining room and kitchen, cozy living room, peaceful courtyard and dozens of bedrooms – was perfect for bringing to life Phillips’ vision. As men, many sentenced to life in prison, graduated from California’s Occupational Mentor Certification Program and said goodbye to their cells for good, Phillips wanted them to have a home that showed them the respect their hard work deserved.

“What I wanted to do with HOPE is I wanted to have OMCP mentors who are coming home from prison to come home to an environment that is the safest, most drug-free, most conducive to successful reintegration into society,” Phillips said.

Nearly three years after opening, about 40 people have graduated from the academy. After six months to two years of support — therapy, food, clothing, housing and lessons in digital and financial literacy, among other skills — they’ve settled into their independence while continuing to serve the community as professionals helping others get or stay clean.

Five men at different stages of the program sat around a collection of plastic fold-out tables in the convent’s former chapel one Monday afternoon. Surrounded by white boards and stained glass windows, they talked about repenting for their crimes, the moment they realized they wanted to make a change and what that change meant for them.

It’s an example of the type of vulnerable conversations residents at the Academy of HOPE have regularly, a skill they began honing on prison grounds across the state.

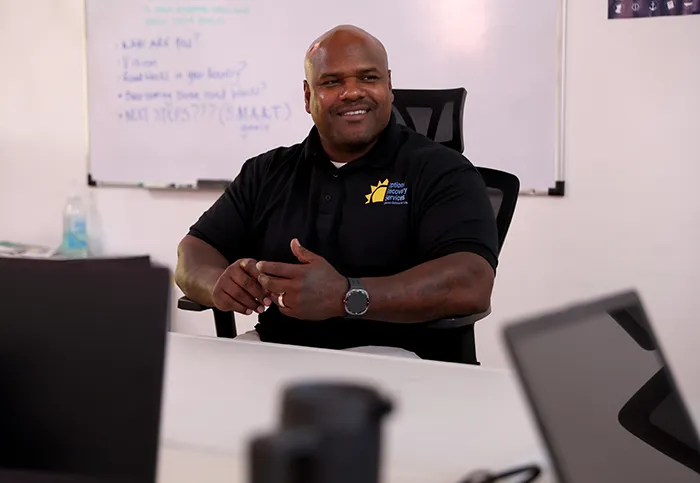

Smith, who led that conversation, is the academy’s director of reentry and violence prevention. Not long after meeting Smith, Phillips said he knew he was the perfect person to help build the program out.

“He’s really been a champion for not just reentry but really the value of the returning person into society who wants to do something better with their life,” Phillips said. “George came out blazing. He shines too bright to keep him contained.”

Experience in counseling and bridge-building started years ago for Smith, long before he became a husband, a beaming new father and a growing leader at Options Recovery.

Before playing an integral role at Options Recovery, Smith spent 25 years in prison. The once bookish boy who was good at school, enjoyed reading, writing and riding his bike, and dreamt of becoming a Marine, a judge or a BMX rider, was primed for prison all his life, he said, and was ultimately sentenced to double life and 44 plus years for the murder of one man and the attempted murder of three other people. He was just 17.

“Ultimately, I just gave up on myself,” Smith said. “The identity of the gang felt so much better than the oppression of just being George.”

It would take another 17 years after Smith first stepped on prison grounds in 1996 for him to have his own revelation. After a near-fatal attempt to smuggle drugs into prison and learning his little brother had followed in his footsteps, serving his own sentence of 235 years to life, Smith made a promise to God that he’d change.

Committed to self-help, Smith began seriously participating in rehabilitation and was accepted into the Occupational Mentor Certification Program after years of good behavior. Smith spent about 20 months at California State Prison, Solano, where he went through training before returning to California Men’s Colony in San Luis Obispo to help counsel others who were incarcerated.

A state decision to dismantle its sensitive needs yard program, which separated people believed to be at high risk of being harmed from the general population, gave Smith the chance to use his connections from dealing and new expertise for a better cause.

Sprawled out on his bunk, Smith developed G.R.O.W, Growth Reinforces Our Worth, a program he used to organize other incarcerated men and welcome new prisoners more peacefully than what was seen at other prisons.

On the same grounds at the time, Tomas Martinez, the academy’s program manager who served 42 years, about 26 of which were in solitary confinement, said Smith “prevented a lot of violence,” and saved lives.

“We had the most successful transition in the state of California, earning me my freedom and the freedom of other men,” Smith said.

That experience also earned Smith a job with Options Recovery Services immediately upon release. Today, GROW is an official LLC focused on mentorship and early intervention for at-risk, or at-promise youth, as Smith says.

Between his work with both organizations, starting his family, coordinating community clean-up days and mentorship with Oakland’s Tiny Homes program, Smith’s life has become one of service. It’s a vast change he credits to Options Recovery Services founder Dr. Davida Coady and her husband and former Options Executive Director Tom Gorham.

“It takes a lot to say, ‘Man, I’m gonna trust that you’re gonna come home and do the right thing,’” Smith said. “They really blessed our lives and in turn we’re blessed, having babies, working hard, and pouring into the community because somebody had a vision.”

Men like Smith, Martinez, Timothy Steer, the academy’s home manager who served 26 years, and Eugene Rayford and Al Strauss, current program participants who served 32 and 13 years respectively, were once considered “unredeemable,” “unhelpable, society’s bad guys,” Phillips said.

But they’ve paid their time, said Martinez. Having been imprisoned at 18 years old and released at the age of 60, he said he gave formative years, never having had a family or hitting other major milestones, deservingly so in exchange for the harm he caused.

Now, Martinez said he and others like him at the Academy of HOPE and other reentry programs have made it their mission to use their stories to help those at risk of going down the same path.

“There’s no throwaway people,” Martinez said. “I’m an example of that.”