Darryl Thomas had a good life. And then, mainly because of serious health issues, he didn’t.

But now, with the help of a Livermore homeless advocacy group, he is getting back to a happier life.

Thomas, 77, is one of 28 residents ranging in age from 30 to 81 currently living at Goodness Village, a nonprofit supportive housing community founded in June 2021 on the grounds of CrossWinds Church. The program serves people who have experienced chronic homelessness, severe mental health conditions, substance use disorders or prolonged housing instability.

“Goodness Village grew from a desire to create a program that treats neighbors as people first, rather than problems to manage,” said executive director Kim Curtis. “While I did not personally experience homelessness, I have long worked with people who have faced the same challenges our neighbors experience today, and I saw a need for a truly low-barrier, supportive community in the Tri-Valley.

“We have supported around 50 neighbors over the past four years in stabilizing their lives, building community connections, and pursuing employment or other personal goals.

A full-time case manager works individually with each resident to develop care plans and connect them to services and a three-tier vocational program that helps residents build skills and transition toward employment.

Thomas was born and raised in the East Bay and graduated from St. Mary’s College. After trying several different careers, he became a real estate agent and loan officer, and life was very comfortable. He had gotten divorced about six years earlier and had had no recent contact with his former wife and their four daughters.

Things began to unravel in May 2003 when he decided to become an independent broker and sought medical insurance. He disclosed that he was a diabetic — a pre-existing condition that made coverage difficult and expensive to attain. So he decided to forego health insurance.

In 2008, he was diagnosed with stage three prostate cancer, and medical bills soared to more than $1 million, which went unpaid, he said. He lost his home in Dublin in 2011, six years before it would have been paid off.

He started living with a family in Sunol, but that did not work out, so he began living out of his SUV. He suffered a blood infection in November 2019 that put him in a hospital for nine months, and later contracted COVID-19, which resulted in pneumonia and another infection — and another hospital stay.

He began living out of another vehicle in July 2020, and did so for more than two years before someone called him and asked if he had ever heard of Goodness Village. He had not, but learned more and eventually became a resident there in May 2023. Today, his unit has all the conveniences he needs. “It is perfect for me,” he says.

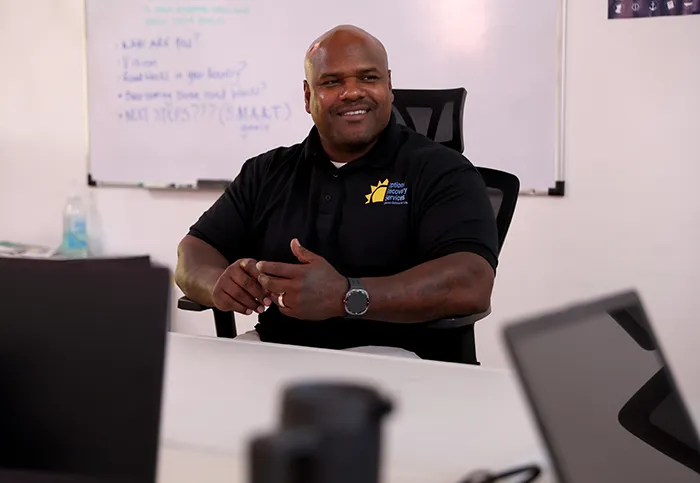

He has become, according to Curtis, “a cornerstone of our community.” He is one of six village council members, an advocate for his neighbors and a regular presence at wellness workshops and community events. “Most importantly, he uses his voice to challenge the harmful stereotypes about homelessness — bringing dignity, insight and hope to every room he enters,” Curtis added.

Thomas says he is “kind of stunned” by the staff’s glowing words. “That makes me feel good.”

He said Goodness Village “is amazing. It’s not for everybody, but it’s a stepping stone in the right direction. They are very supportive here and your best interests are their main concern.”

He said what stands out, in addition to 24-hour personal onsite support, is a “plethora of services for those inclined to use them,” including help with Social Security benefits, food stamps, SDI, job assistance, finances, and medical and vision needs. There are also ride shares and connections for other services such as food, clothes and doctors’ appointments.

“You can’t go hungry here,” he says.

There is a sliding-scale fee for residents based on any income they have. Thomas, who said “I lost everything,” now gets a monthly Social Security check, gardens and takes care of chickens that are raised there.

He is still a bit unsure of what the future holds — “I’m the second oldest person here and I’ll probably not leave here” — but he is extremely grateful to be a resident and for the help he has received: “I’m back on the road to getting where I want to be.”

Goodness Village is led by Curtis, who has a doctorate in human services and is also a licensed clinical worker. The village was the idea of the church, which recruited her. Its primary funding sources for its annual budget of $1.4 million are donations and grants.

“We are small but mighty,” Curtis said, “and our approach is proactive and supportive rather than reactive and punitive, focusing on dignity, safety, and community.”

Residents can remain in the Village without a fixed timeline, provided they engage in the program and contribute positively to the community, she said. The goal is to help each person rebuild their life and avoid returning to homelessness. Many are on waitlists for permanent affordable housing, which can be lengthy.

Curtis, who has worked in reactive systems of care such as locked mental health treatment facilities and jails, said she is “overjoyed to work in a proactive village where crises are nearly non-existent because access to support is readily available with the 24-hour staff. People hold the keys to their own safe space, which is a stabilizer for people who have survived trauma and abuse.”

“At the village, we know our neighbors are the most resilient and the best experts of what they need; we literally give them the keys and the support needed to control their own story. The success is theirs, not the staff’s. Our joy comes not from people transitioning out of the village but from our neighbors stepping back into ownership of their futures, engaging in recovery and building community.”